Economists have a bit of an image problem. People think we shamelessly massage statistics, overconfidently make terrible predictions, and are no fun at drinks parties.

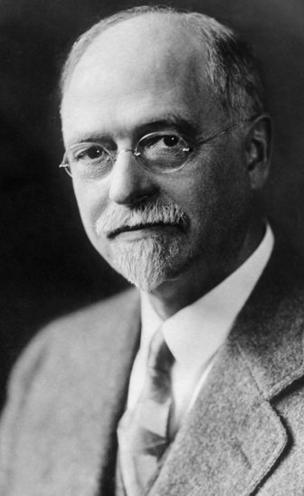

Perhaps some of the blame for this lies with the man who, a century ago, was probably the most famous economist in the world – Irving Fisher.

It was Fisher who notoriously claimed, in October 1929, the stock market had reached “a permanently high plateau”.

Nine days later, came the huge stock market crash that led to the Great Depression.

As for parties, the best that can be said for Fisher was he was a generous host.

As Mark Thornton records in The Economics of Prohibition, one of Fisher’s dinner guests wrote: “While I ate right through my succession of delicious courses, [Fisher] dined on a vegetable and a raw egg.”

A fitness fanatic, he avoided meat, tea, coffee and chocolate.

He didn’t drink alcohol either, and was an enthusiastic supporter of prohibition, America’s ill fated attempt to outlaw its manufacture and sale, which began in 1920.

It was a remarkable change – the country’s fifth-largest industry was suddenly made illegal.

Fisher predicted it would “go down in history as ushering in a new era in the world, in which accomplishment this nation will take pride forever”.

He added he couldn’t find a single economist willing to oppose the policy in a debate.

In fact, prohibition turned out about as well as his prediction about the permanently high plateau: historians typically regard it as a farce.

It was so widely flouted alcohol consumption decreased by only about a fifth. It finally ended in 1933, when one of Franklin D Roosevelt’s first acts as president was to re-legalise beer, bringing cheering crowds to the White House gates.

The roots of prohibition are generally traced to religion, perhaps laced with class-based snobbery.

But economists had another concern: productivity.

Wouldn’t sober nations outcompete those with a workforce of drunks?

Fisher certainly seems to have happily taken some liberties with figures. He claimed, for example, prohibition was worth $6bn to America’s economy.

Was this figure the result of careful study? Not according to one bemused critic.

Evidently Fisher started with reports from a few individuals a stiff drink on an empty stomach made them 2% less efficient.

He then assumed workers habitually downed five stiff drinks just before work, so multiplied the two by five and concluded alcohol lopped 10% off production.

Dubious, to say the least.

Economists might have been less surprised by the failure of prohibition if they’d been able to fast-forward half a century to economist Gary Becker’s Nobel Prize-winning insights on “rational crime”.

Becker said making something illegal simply added another cost rational people would weigh up alongside other costs and benefits – the penalty if you’re caught, modulated by the probability of being caught.

He meant it, too: the first time I met him, he parked his car in such a way he risked a ticket. “I don’t think they check that carefully,” he told me, cheerfully admitting he had committed a rational crime.

“Rational criminals,” said Becker, “will supply prohibited goods at the right price.”

Whether consumers will pay that price depends on what economists call elasticity of demand.

Imagine, for example, the government bans broccoli. Would “black marketeers” grow broccoli in secluded back gardens and sell it down dark alleys for an inflated price?

It’s unlikely, because demand for broccoli is elastic – hike the price and most of us will buy cauliflower or cabbage instead.

With alcohol, it turns out, demand is inelastic: raise the price and many will still pay it.

Prohibition was a boon for rational criminals such as Al Capone, who defended his bootlegging in entrepreneurial terms.

“I give the public what the public wants,” he said. “I never had to send out high-pressure salesmen. I could never meet the demand.”

America wasn’t the only country to try prohibition – others included Iceland, Finland and the Faroe Islands – but nowadays nations that strictly ban alcohol tend to be Islamic.

Others have partial restrictions. In the Philippines, for instance, you can’t buy alcohol on election day, or in Thailand on Buddhist holidays – except at the airport duty-free. America still has some “dry” counties, and local “blue laws”, which ban sales on Sundays.

The idea is regulations are often supported by a surprising alliance of noble-minded moralists and profit-driven cynics.

Think about bans on cannabis. Who supports them?

In recent years, that alliance has weakened: cannabis has been legalised or decriminalised from California to Canada, from Austria to Uruguay.

Debates in other countries are raging: if you’re going to impose costs on cannabis producers, should you do that by trying to enforce laws against selling cannabis, or by making it legal and imposing a tax?

- Why are so many countries now saying cannabis is OK?

- Teens less likely to use cannabis when it’s legal, US study finds

- Should cannabis be legal in the UK?

In the UK, the free market think tank the Institute for Economic Affairs has crunched the numbers on elasticity of demand for cannabis.

It reckons a 30% tax would almost eradicate the black market, raise about £700m – almost $1bn – for the government, and lead to safer drugs too, just as the end of prohibition led to safer alcoholic drinks.

Today, you’d have no trouble finding economists to oppose the prohibition of cannabis: at least five Nobel Prize winners have called for an end to the “war on drugs”, arguing instead for “evidence-based policies underpinned by rigorous economic analysis”.

Naturally, that evidence covers productivity. Some studies find cannabis impairs function; others find no effect.

One slightly implausible outlier even found smoking a joint gave a short-term boost to workers’ hourly output.

Source: BBC NEWS